Month: October 2018

NetBIOS

NetBIOS over TCP/IP (NBT, or sometimes NetBT) is a networking protocol that allows legacy computer applications relying on the NetBIOS API to be used on modern TCP/IP networks.

NetBIOS was developed in the early 1980s, targeting very small networks (about a dozen computers). Some applications still use NetBIOS, and do not scale well in today’s networks of hundreds of computers when NetBIOS is run over NBF. When properly configured, NBT allows those applications to be run on large TCP/IP networks (including the whole Internet, although that is likely to be subject to security problems) without change.

NBT is defined by the RFC 1001 and RFC 1002 standard documents.

NetBIOS provides three distinct services:

- Name service for name registration and resolution (ports: 137/udp and 137/tcp)

- Datagram distribution service for connectionless communication (port: 138/udp)

- Session service for connection-oriented communication (port: 139/tcp)

DNS MX records

source

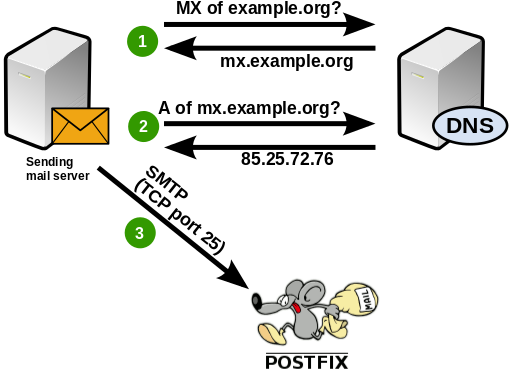

So now you have your working mail server. But how do emails find you? The answer lies in the most important service on the internet: DNS. Assume that you are the owner of the gmail.com domain. And a mail server somewhere on the other end of the internet wants to send an email to john@example.org. What the other mail server needs to do is find out which server on the internet it will have to establish an SMTP connection to in order to deliver the email. Let’s reiterate how that happens:

The remote server queries its DNS server for the MX (Mail eXchanger) record of the “example.org” domain. If no MX record was found it tries again and asks for A (address) records. Let’s run a query for a real domain to get an idea:

$> host -t MX gmail.com

gmail.com mail is handled by 10 alt1.gmail-smtp-in.l.google.com.

gmail.com mail is handled by 20 alt2.gmail-smtp-in.l.google.com.

gmail.com mail is handled by 30 alt3.gmail-smtp-in.l.google.com.

gmail.com mail is handled by 40 alt4.gmail-smtp-in.l.google.com.

gmail.com mail is handled by 5 gmail-smtp-in.l.google.com.

So as a result we get 5 different MX records. Each of them consists of a priority and the host name of the mail server. A mail server would pick the entry with the highest priority (=the lowest number) and establish an SMTP connection to that host. In this example that would be the priority 5 server gmail-smtp-in.l.google.com. If that server could not be reached then the next best server with priority 10 would be used and so on. So all you have to do in your own DNS zone is add an MX entry pointing to your mail server. If you want to run a backup mail server (which is outside of the scope of this tutorial) then you can add a second entry with a an equal or lower priority.

A mistake some people make is using an IP address in MX records. That is not allowed. An MX record always points to a host name. You will have to add an A record for your MX record to point to the actual IP address of your mail server.

(In the above example it is very unlikely that a mail server will ever have to use the server with priority 40. Adventurous system administrators can add such a low-priority entry and see who connects to it. An interesting observation is that spammers often try these servers first – hoping that it is just for backup purposes and less restrictive than the main server. If you see someone connecting to the lowest-priority address first without having tried a higher-priority mail server then you can be pretty certain that it’s not a friend who’s knocking at your door.)

Fallback to A entries

It’s always best to explicitly name mail servers in the MX records. If you can’t do that for whatever reason then the remote mail server will just do an A record lookup for the IP address and then send email there. If you just run one server for both the web service and the email service then you can do that. But if the web server for your domain is located at another IP address than your mail server then this won’t work.